Cometary plasma environment studied by the Rosetta spacecraft

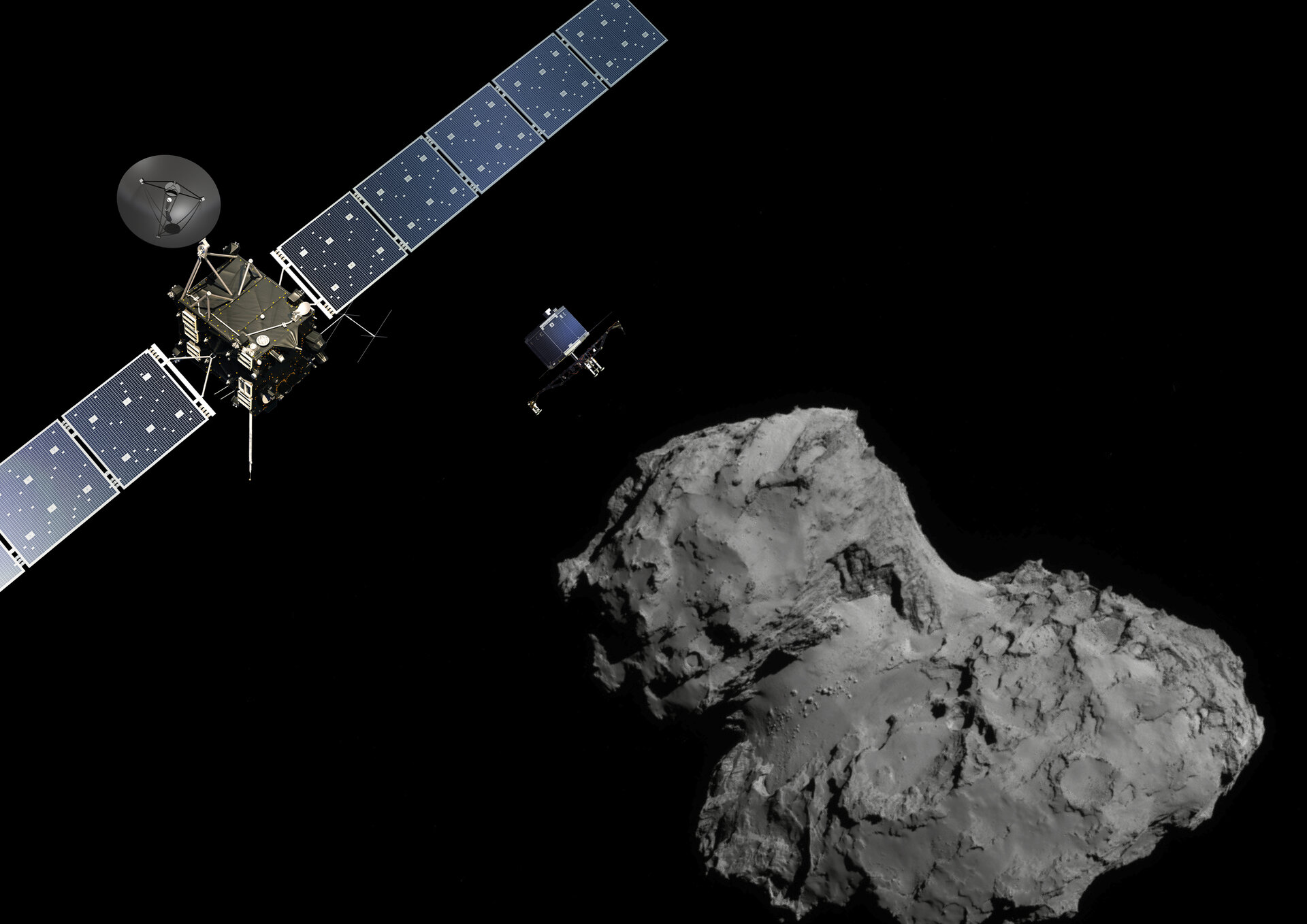

After 10 years in space, the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Rosetta had finally rendezvoused and then accompanied comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on its journey around the Sun. Its mission was to explore an ancient and mysterious frozen world formed at the beginning of the solar system, more than 4.5 billion years ago, and investigate the origin of life and water in the Solar System. To do it, we had a set of more than 20 very sensitive instruments measuring the composition and properties of the cometary environment and surface, placed on the orbiter Rosetta and its small lander Philae. It was an extraordinary way of exploring a comet, as it was the first time ever a spacecraft travelled with the comet and could follow its evolution.

From August 2014 to September 2016, the mission revealed a complex cometary history, and had a few technological firsts: first mission orbiting a comet, first landing on a comet nucleus (in November 2014), first in-situ measurements of the comet as it is transformed from a mostly inactive frozen body to a full-fledged comet with its characteristic tail (or coma) when coming closer to the Sun (2014-2016). The comet was found to be a true primordial object, a time-capsule of the early solar system, that has almost not changed since its formation. Its brand of water (isotopic content) does not resemble that of Earth, which implies that the reservoir of water where the comet formed has contributed very little to the appearance of water on the early Earth, when the planet was bombarded by myriads of asteroids and comets. Interestingly, the Rosetta teams also found complex organic molecules, such as glycine (the simplest amino-acid), which suggests that space rocks such as comets could have been responsible for bringing the building blocks of life to Earth.

One of the instruments onboard Rosetta has been co-developed at the Department of Physics of the University of Oslo (UiO) and was a part of the Rosetta Plasma Consortium (RPC) on the orbiter. This suite of sensors within RPC measured the charged particle environment of the comet (called a “plasma”) and characterized the electromagnetic activity around it.

In this project, we analyzed data from the instruments onboard the Rosetta spacecraft and developed numerical models to interpret the in-situ environment of the comet on its way around the Sun. We also investigate how small cometary dust particles move and interact with the surrounding plasma, and how they are being electrically charged in complex plasma environments. Because the cometary coma is ever changing and is responding and continuously adapting to the Sun’s influence (the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation and the solar wind, a stream of fast electrons and ions flowing out into space), such a characterization is invaluable when it comes to understanding the formation, the life and the future of a comet. We have also studied how the instruments behave in complex plasma environments, in order to improve our data analysis techniques, not only for Rosetta, but also for other spacecraft. The project at UiO has thus contributed to our knowledge on the cometary environment composition and its evolution, the small dust particles in plasma, and measurements with instruments onboard spacecraft.